This is the eulogy I gave for Mum on Friday 11 May at St Mary’s Hornby.

Forty-five years an item, Mum and Dad. Forty years a mother. Seven years a grandmother. Mum’s life encompassed many other parts: an intrepid traveller, who in the sixties journeyed on the Trans-Siberian railway before hitchhiking across Scandinavia; newsdesk secretary; chorister; volunteer and then computer expert for Citizens’ Advice; cross-country skier; desktop publishing whizz; yachtswoman; and then in her retirement working out her flair for interior design by transforming Holtby Hall from its run-down state in 2000 to its present beauty.

She was born in Merton, South London, a month before VE Day, to Philip and Margaret Lewis. Her father was in the RAF ground crew, fixing radios. After the war they lived a hand-to-mouth existence as he trained to be a pharmacist, studying in Portsmouth during the week and then cycling 50 miles back to London to see his family. Mum desperately wanted a brother or sister, and was heartbroken at the age of nine when a younger brother, Nigel, died at birth. She told schoolfriends she would have lots of children when she grew up, though Mum and Dad never quite made it to her original target of four.

At school, mum had a flair for art, and was grabbed by English literature. She learned calligraphy, which she would later try to teach her children, without much success. Schoolfriends remember mum having a sharp sense of humour, and an independent spirit that led to battles with her mother. When Mum was loaned an “advanced” book by Emile Zola, Granny burned it. Mum’s interest in Shakespeare confronted Granny’s view, possibly not helped by the BBC’s “Wars of the Roses” dramatisation, that the plays were “a load of bloodthirsty rubbish.

Even at school she was an adventurous traveller, going round Ireland with friends in a caravan pulled by a dim carthorse that stood on her foot one morning then refused to move; getting lost on the Paris metro. In 1962 she returned from a week-long trip to Malham Tarn to find her parents and friends shaken. Without newspapers, radio or television for a week, she had been completely unaware of the Cuban Missile Crisis bringing the world to the edge of nuclear war.

Like her father, mum was in the top stream at her school. But like him, she didn’t have the option of university: she said it wasn’t even suggested. Instead she trained as a secretary, went to work for the BBC, and set her mind to travelling.

Just before her 21st birthday, Granny and Grandad, were persuaded to sign the consent forms and in 1966 Mum became one of the Ten Pound Poms who took subsidised flights to Australia. Her plan was to work enough to fund more travel, and she wasn’t put off by obstacles. When, with three friends, she set off to drive to Ayer’s Rock, she didn’t let the fact that she didn’t have a license stop her from taking her turn behind the wheel as they covered the hundreds of miles.

Later on, she would tell us about the jobs she had: the boss whose thick accent made his instructions so incomprehensible that, in the end she filed his correspondence in the ladies’ loo and quit; or working for the composer Peter Sculthorpe, who told her over a gin and tonic on his 40th birthday that he’d realised no one would ever again call him a promising young composer.

My own first experiences of a newsroom were second hand, from her days as the secretary at the Sun-Herald in Sydney. Newsmen in the sixties were a hard-bitten lot, and Sunday journalists, who can drink from Tuesday to Thursday without having to file a word, the hardest of the lot. Like all editors’ secretaries, she opened her share of letters, invariably on lined paper and in green ink, that began, “To whom it may concern, I have recently been abducted by aliens.” When, new in the job, she consigned a set to the bin, her boss stopped her. “Oh no,” he said. “We print all those. We’re Australia’s Official UFO Paper.”

Mum met Dad at a party in Sydney in late 1966. He too had arrived in Australia looking for a break from England (but as a free citizen, not a ten pounder) and had landed a job with IBM. He was the third man to call her after the party, but the one she had liked.

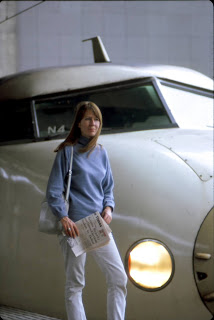

According to Mum, at this time Dad was living largely off Digestive biscuits. Once a week, she said, he would put a bird into the oven and burn it. If it was obvious to her that he needed domesticating, it wasn’t so clear to him. By mid-1968, Mum had, Dad says, got fed up with Australia. In her account, she’d got tired of waiting for him to make up his mind about her. She set off for home, with Japan as her first stop. Dad set off in pursuit, and on a rowing boat in the middle of a lake near Tokyo, he proposed marriage, and she accepted.

While Dad returned to Sydney, Mum stuck with her travel plans: by air to Vladivostock, by the Trans-Siberian Railway to Moscow, on to Leningrad, as it then was. As she travelled across Russia, she had her camera confiscated for photographing the wrong bridge, and an encounter with a young woman she later decided was probably trying to entrap her into breaking laws against the black market. From Russia she flew to Helsinki, and then hitchhiked through Sweden before returning to London for what may have been the most daunting journey of all: to Yorkshire, to meet her future in-laws, and see what she didn’t know then would be her final home.

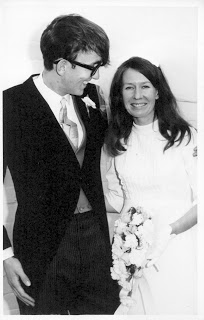

Mum and Dad married in Sydney on the 30th November, 1968. She didn’t want to work as a secretary again, so Dad suggested she try Macquarie University. She had a thoroughly enjoyable year getting a fresh perspective on the study of history, before they decided in 1970 to move back to England to raise a family, a journey that took them through Cambodia, Thailand, India, Nepal, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey. The houses we grew up in had small, beautiful souvenirs of these travels everywhere.

The Seventies saw the arrival of first Julia, then me, then Hilary, and moves to Harpenden and Sheffield. Mum still found time around children to complete, through the Open University, the degree course she’d started in Sydney, even if it involved the odd midnight dash to submit an essay. Her enthusiasm for learning never dimmed: in later life she became a whizz with computers, and when she fell ill she had been attending Latin classes.

In 1980, we moved to Gerrards Cross. Mum made money stretch, decorating one room of the house herself at a time over a period of years. She was amused by the pretensions of South Buckinghamshire, always happy to manoeuvre our ancient Saab 99 past Mercedes and Jaguars stuck in the snow and ice. Her concession to the girls’ frightfully posh school was to clean the rust off the side of the car that the headmistress would see. At my own slightly more relaxed school, the car door fell off one day as I was getting out, and to Mum’s delight, the maths teacher tied it back on with some rope.

Once Hilary had started school, Mum looked about for a way to make herself useful, and settled upon becoming a volunteer at the Citizens’ Advice Bureau in Uxbridge, where she’d work for more than a decade. It was tough work, often depressing, especially in a period of rising unemployment and recession, but she found it immensely stimulating. For her children, too, it was educational: we became school experts on the world of multiple debtors and landlord and tenant, absorbing titbits over dinner – “you never have to let the bailiffs in”; “wait for the solicitor before you say anything”.

Having a part-time working mother provided new experiences for the three of us: M&S pizzas on working days, after walking ourselves home. Mum faced the same school holidays problems as today’s working parents. But social services being less militant then, and childcare less easy to come by, the three of us would simply be left in Uxbridge library for the day, where we worked our way through the children’s section.

Mum found friends in Gerrards Cross. “You couldn’t help but be fond of her,” one said to me last week. “She had a lovely way of putting things, and a laugh in her voice. Her laugh would come into the room first and she would follow.” She regularly hosted evening meetings of the National Housewives Register, known to those of us upstairs as “the chatter-chatter-ha-ha bunch.”

She was equally welcoming to our friends, and then boyfriends and girlfriends, and finally sons and a daughter-in-law. A devoted grandmother, she was always supportive, never criticizing our decisions as parents.

Throughout her life, Mum found new enthusiasms. Some, like the flute lessons, didn’t take off, others did. In her 40s she took up first dinghy sailing and then yachting, leading to many happy holidays on the Mediterranean. Her spirit was summed up in the name she chose for her dinghy: “Carpe Diem.”

But Mum wasn’t without anxiety about the world. Years before it was possible to share tales of unlikely disaster on the internet, Mum would carefully clip stories of children injured by swallowing magnets or blinded by biros, ready to be produced at relevant moments. It was typical of Mum’s good humour that she was happy to join the rest of us in referring to this folder as “The Woe File.”

It was Mum, not school, who introduced us to Shakespeare and Austen, and to another passion, classical music. The arrival of the Prom program in the house was an annual event. Over the decades she sang alto in a series of choirs, always maintaining that she was mainly following the person next to her.

In 2000, Mum and Dad made their final move, from Gerrards Cross up to Holtby. The house at that stage had serious structural problems, and hadn’t been redecorated in years. It was a great canvas for Mum to work on, and every beautiful room bears her mark. Travel now meant cross-country skiing in Norway, two return trips to Australia, and driving across the Rockies to San Francisco.

Though theoretically in retirement, Mum continued as active as ever, organising Christian Aid collections just as, in previous decades, she’d help collect and sort donations to jumble sales. She returned to painting, an early passion, with one local group, and joined also a sewing circle. The last time we came to this church with her, at Christmas, she proudly showed her granddaughter Miranda the sheep she’d embroidered on the banner.

The final decade of her life saw her becoming a grandmother, first to Miranda, then to Fraser, Rachel, Lizzie, Cameron, Dora and Thomas. Even at a distance from London, she was always willing to help out, until ill-health intervened. One of her few unhelpful interventions was teaching her grandchildren to pull rude faces.

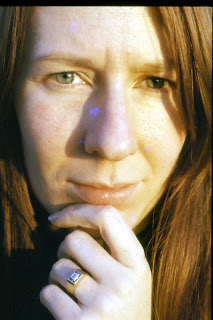

I realise now that I didn’t really think about who Mum was, in the way that I don’t really think about the ground: she was the solid thing upon which so much of my life has always rested. Talking to friends who knew her, they’ve repeatedly mentioned things I took for granted: her warmth, her ability to see the funny side of anything, her spirit of adventure and willingness to try new things.

When she told us about her terminal diagnosis, in February, she insisted she had few regrets in her life. “I wish I’d painted more pictures, sung more songs,” she told Julia. She was sad to be leaving us, but she said she’d rather leave a shorter life that she’d enjoyed than have had a longer and less happy one. We will miss her desperately, but we shall remember her smiling, as she so often was.